Health communication

Dengue Fever: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

Classification

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne viral disease common in tropical regions. It is caused by the dengue virus, transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Symptoms vary from mild fever to life-threatening conditions, so early diagnosis and proper management are essential. According to the Ministry of Health and WHO, dengue is classified into three levels: dengue fever, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue.

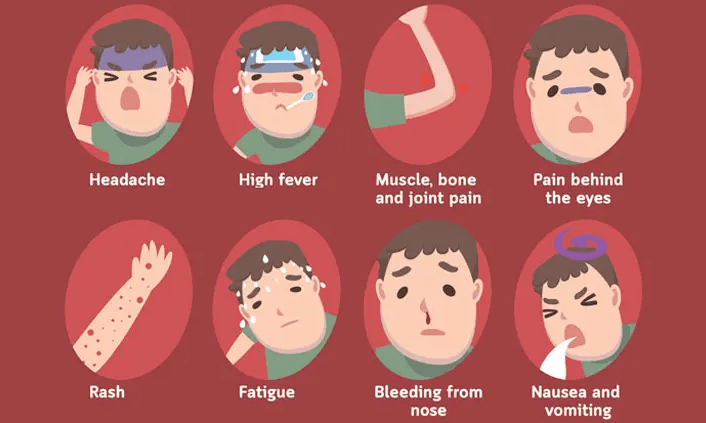

Dengue fever usually occurs in people living in or visiting endemic areas. Typical features include sudden high fever lasting up to seven days, along with nausea, vomiting, rash, muscle or joint pain, pain behind the eyes, or minor bleeding on the skin. Blood tests may show a normal or elevated hematocrit, with low or normal white blood cells and platelets.

Dengue with warning signs includes the above symptoms plus at least one danger sign: restlessness, drowsiness, severe abdominal pain, frequent vomiting, enlarged or tender liver, mucosal bleeding (gum, nose, stomach, intestines, urinary tract, or vagina), reduced urine, a sharp rise in hematocrit with a rapid fall in platelets, AST or ALT >400 U/L, or fluid accumulation in the chest or abdomen.

Severe dengue is the most dangerous form. It may involve severe plasma leakage leading to shock or respiratory distress, heavy bleeding, or organ failure. The liver may show AST or ALT ≥1000 U/L, the brain may be affected with altered consciousness, and the heart or other organs can also be damaged.

Diagnosis

Laboratory confirmation can be made using the NS1 antigen test (days 1–7, best in the first 5 days), ELISA or rapid antibody tests for IgM and IgG from day 5, or PCR during the fever stage. Dengue should be differentiated from other conditions such as viral rashes, hand-foot-mouth disease, scrub typhus, malaria, bacterial sepsis, meningococcal infection, blood disorders, or acute abdominal diseases.

Treatment

There is currently no specific antiviral drug for dengue. Treatment focuses on symptom relief, supportive care, and close monitoring.

Most patients with dengue fever without warning signs can be managed at home. Fever should be treated with paracetamol only (10–15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours, maximum 60 mg/kg/day). Steroids and NSAIDs must be avoided because of bleeding risks. Patients should rest and drink plenty of fluids such as ORS, fruit juice, coconut water, or thin rice porridge with salt. They must return to the hospital immediately if they develop warning signs such as worsening condition despite fever subsiding, inability to eat or drink, persistent vomiting, severe abdominal pain, cold clammy extremities, bleeding, confusion, drowsiness, or no urine for more than 6 hours.

Patients with dengue and warning signs should be hospitalized. Intravenous fluids may be given if the patient cannot drink, is vomiting, dehydrated, drowsy, or has increased hematocrit with falling platelets. IV fluids such as Ringer’s lactate or 0.9% NaCl are started at 6 ml/kg/h for 1–2 hours, reduced step by step as the condition improves, and can usually be stopped after 12–24 hours once vital signs and urine output are stable. Special groups such as pregnant women, infants, the elderly, obese patients, or those with chronic diseases should always be admitted for monitoring.

Severe dengue requires emergency hospital care with intensive supportive treatment and close monitoring for shock, bleeding, and organ failure.

Prevention

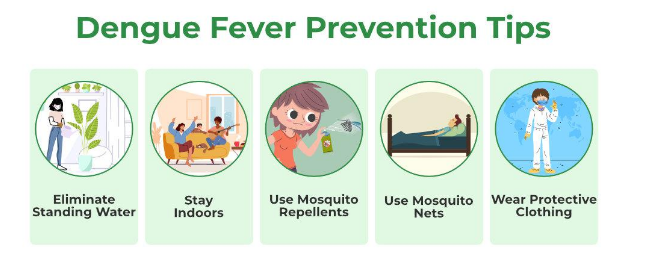

The most effective way to prevent dengue is mosquito control: eliminating standing water, using nets, repellents, and maintaining a clean environment.

Vaccination also plays a role. In 2016, the first vaccine, Dengvaxia, was introduced for people aged 9–45 in high-risk endemic areas. A newer vaccine, QDENGA, is a live-attenuated tetravalent vaccine given in two doses three months apart, and is now available in some countries.

Dengue is potentially dangerous, but most cases can be managed with early recognition, proper care, and community-wide mosquito control. Vaccination provides added protection in certain populations. Protect yourself and your community by seeking medical care promptly and preventing mosquito bites!

References

1. Infectious Diseases, Medical Publisher, 2020.

2. Decision No. 2760/QD-BYT year 2023, Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Dengue hemorrhagic fever, Ministry of Health.

3. Bennett, John E., Raphael Dolin, and Martin J. Blaser. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases E-Book: 2-volume set. Elsevier health sciences, 2019.

4. Roy, Sudipta Kumar, and Soumen Bhattacharjee. "Dengue virus: epidemiology, biology, and disease aetiology." Canadian journal of microbiology 67.10 (2021): 687-702. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2020-0572.

5. Dhole, P., Zaidi, A., Nariya, H. K., Sinha, S., Jinesh, S., & Srivastava, S. (2024). Host Immune Response to Dengue Virus Infection: Friend or Foe?. Immuno, 4(4), 549-577. doi.org/10.3390/immuno4040033

6. Ho Chi Minh City Center for Disease Control. https://hcdc.vn

7. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON518

Mpharm. Kim Ngoc Son

Mpharm. Nguyen Thanh Tam